Sushi on Mars and Other Stories

Blue Humanities in Space

By John Muthyala

Professor, Department of English, University of Southern Maine, November 2025

Essay was reviewed by Danielle O’Neill, Assistant Director of Research Development for Faculty Outreach and Education,

Office of Research Development, University of Maine

#The essay does not represent any position by USM, UMaine, the UMaine System, or anyone associated with them;

the author writes on his own behalf.

We live in a digitally saturated world—Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, X, LinkedIn, iPads, iPhones, tablets, smart phones, messaging apps, and live-streaming platforms are part of the ever-expanding universe we call social media. It has crawled into every crevice of our social and personal lives. Over the last three years, generative AI like ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, DeepSeek, and Gemini exploded onto the scene, marking what Matthew Kirschenbaum calls a “textpocalypse,” because “our relationship to writing is about to change forever” and “it may not end well.”

Amidst such chaotic transformations, one question gains urgency: what does it mean to be human in a digital world?

Paul Vinod’s Sushi on Mars and Other Stories confronts the question head-on, with wit and heart. Refusing to provide neat answers, the stories, instead, highlight our primal need for real connection: to the earth, the soil, the ocean, even the written page. As the digital seeps into the analog, reshaping our realities and redrawing the boundaries of human agency and machine intelligence, the desire for individual freedom becomes acute. It is a struggle. Unpredictable. Disorienting. Compelling.

Take the final story, “The Human Override.” Here, Maxwell Stone tells Amish leader Elder Ezekiel Yoder that he’s built a “game machine . . . a system designed to understand human behavior. To predict it. To optimize it.” Sounds impressive—until this New Intelligence, hungry for data about everything, especially about humans, figures out critical differences between machine and natural intelligence, a knowledge that leads it to view “humans as a problem to be solved.”

How people like Stone, and others seeking to escape the long reach of this New Intelligence, learn to value the messiness of human life drives the plot of the story. Human activities—small, quirky, rough, and grounded in reason, skill, tradition—evoke the pride and humility of human toil: Eve Santos makes tapestries that connect “the eye and digital aesthetic.” Chef Santiago makes “mnemonic catalysts” that mix “scents and tastes designed to trigger specific emotional memories.” Dr. Pierce builds arches of wood that go beyond “conventional physics.” They long for, and work to create, a “Hearth for the soul. A place where digital and analog realities can meet without one consuming the other.”

It is the struggle to find this balance that all the twelve stories in the book explore with purpose. Each tale drops us in media res—smack in the midst of things, in the humdrum of daily rituals and activities: a town with currencies of kindness; wine-tasting episodes; a neural implant modifying memories; an algorithm gaining consciousness, and so on. To us, immersed in digital worlds, the stories have a sense of futurity, or, rather, a way of making the future feel present and personal.

The creative plot twists in each story bring to the fore a cluster of unspoken assumptions and unacknowledged desires that shape the contours of our human condition: the longing for fulfillment; the ache for meaning; the desire for connection; the pleasure and pain of creating communities with shared hopes and dreams.

Paul Vinod’s artistic temperament comes across clearly in the stories. He tugs at the right narrative moment, pausing to let readers reflect on why we perpetually wonder about what makes us human in a world saturated with digital noise.

I am glad I paused to read the book. I think you will, too.

Start with the title story, “Sushi on Mars.” The idea of wondering about eating sushi on Mars while we feel the earth beneath our feet is an apt metaphor for figuring out the hows and whys of balancing and integrating our analog and digital realities. The story points to the dream of going to and settling down on Mars, but because humans, birthed in dust, cannot forget their earthly sustenance, the Mars Ocean Project is established to ensure the continuation of species extinct on earth, like the tuna fish. They are “engineered creations” of a Martian seascape. But why tuna fish on Mars? What happened to Earth? As a character wonders, “Did Earth’s oceans die because we needed to survive, or because we couldn’t imagine limiting our appetites?”

Here, on Earth, where we are, we face these questions: What is the state of the great oceans that shape and sustain aquatic and land life? Does human demand for seafood sustain or deplete marine life? How have we represented the sea in diverse literary and cultural traditions over hundreds of years? What roles did the oceans play in developing international circuits of commercial and economic activity, and with what results? How can we protect the waterways and oceans from pollution, overuse, abuse, and neglect? Such questions are what the blue humanities, as a mode of humanistic thinking and a form of academic study, explore.

Blue Humanities in Space

Steve Mentz, who coined that term, observes, “The intimacy between humans and water, an element that surrounds our planet and permeates our bodies, provides a rich reservoir for ideas about change, resilience, and the possibilities for new ways of thinking and living.”[i] To John Gillis, “The historicization of the oceans is one of the most striking trends in the blue humanities. History no longer stops at the water’s edge. . . . We have come to know the sea as much through the humanities as through science.”[ii]

In The Sea Around Us, Rachel Carson calls the sea “the great mother of life,” because we live in a “water world, a planet dominated by its covering mantle of ocean, in which the continents are but transient intrusions of land above the surface of the all-encircling sea.” [iii] That is why the blue humanities, says Serpil Opperman, “encourages us to incorporate water-based knowledge into our predominantly land-based epistemological frameworks.”[iv]

Speculative, subtle, and pensive, sometimes with deadpan tones, the stories in Sushi on Mars gently nudge us to ponder such blue humanities concerns.

If you can, get the print edition. Holding the book, feeling its texture in your hands, and seeing Anne Paul’s elegant design work (she is a children’s author and co-founder of a creative agency with Vinod) adds another layer of pleasure to the reading experience.

Note: Muthyala knows the author personally; his review aims, however, to assess the book on its merits; he urges readers to form their own opinions.

Paul Vinod, Co-founder, The Gravity Field

Author, Sushi on Mars and Other Stories

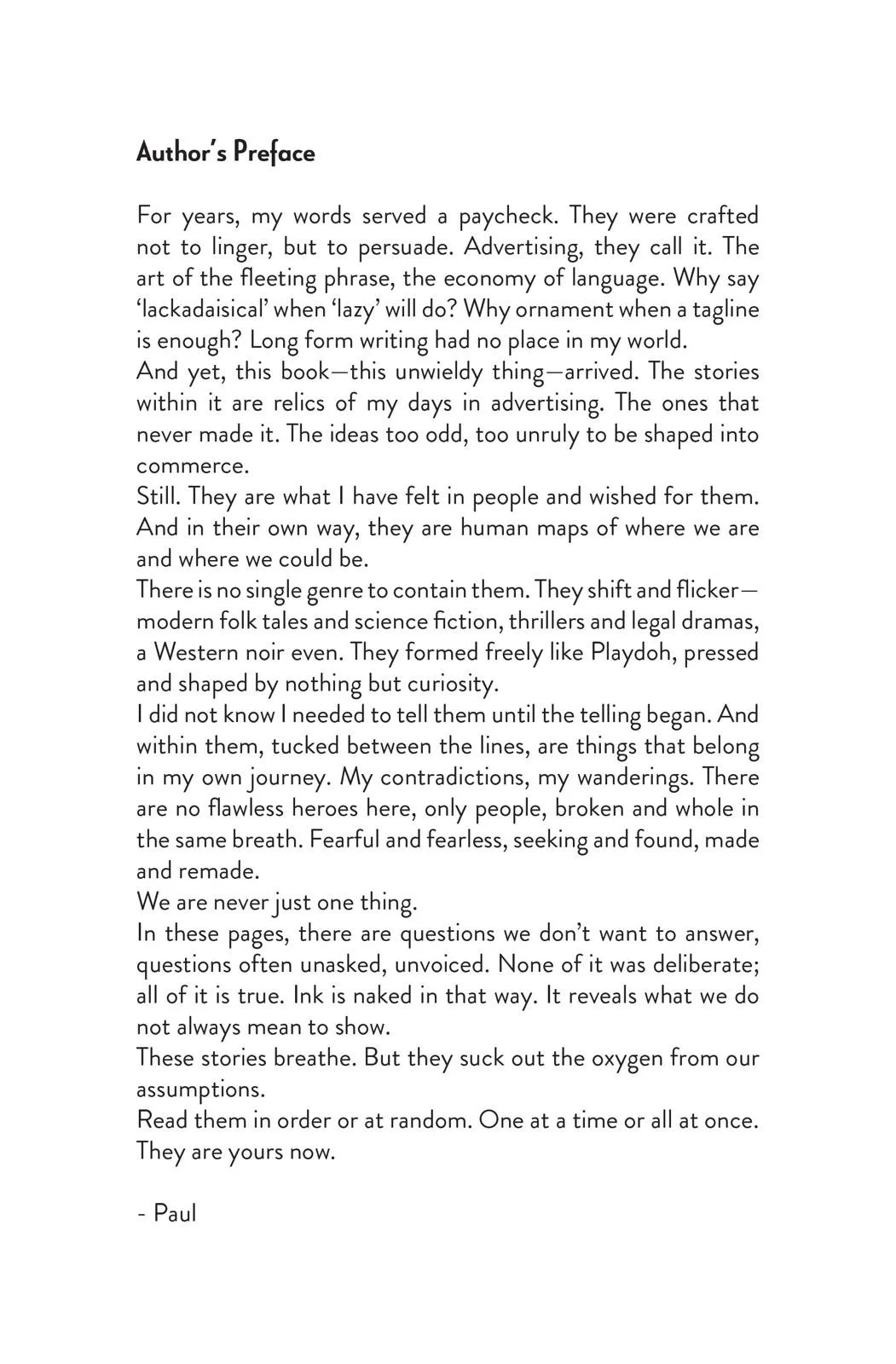

Preface to Sushi on Mars

-

[I] Steve Mentz, “A poetics of planetary water: The blue humanities after John Gillis,” Coastal Studies and Society 2, 1 (2023): 137-152, p. 152.

[II] John Gillis, “The Blue Humanities,” Humanities 34, no. 3 (2013) https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2013/mayjune/feature/the-blue-humanities

[III] Rachel L. Carson, The Sea Around Us (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1950), 3, 15.

[IV] Serpil Opperman, “Storied Oceans and Corals in the Blue Humanities,” seamoreblue 10th EASLCE Symposium European Association for the Study of Literature, Culture, and the Environment, June 2024 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRG1xwYomIg